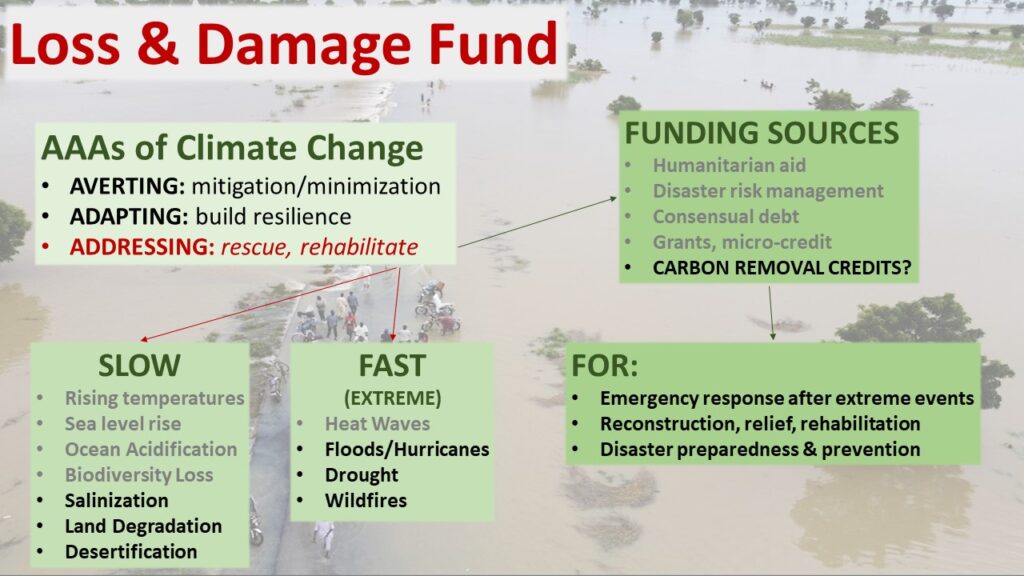

“Loss & Damage” is a relatively new term within the climate community. It refers not just to the impacts being experienced ever increasingly as a result of too many heat trapping gases in the atmosphere, but also to the activities which can and should be undertaken to address these impacts, whether they are sudden or slow, after they occur. Importantly, it also seeks to address how those activities are funded. It is focused on insuring and assisting those suffering the most from climate change that contributed the least to emitting excessive carbon into the atmosphere. This pool of funds is completely separate from funding aimed at helping countries to either reduce emissions or proactively adapt to expected changes.

Perhaps unsurprisingly the amount of funds pledged by high emitting countries to date is woefully inadequate to meet the escalating costs of rescuing communities that have been hit by extreme events exacerbated by increased atmospheric GHGs. A recent example is huge flooding due to excessive rains in 2022 in Pakistan which caused more than $30B in damages and affected tens of millions of people. The US contributed less than $100M to recovery efforts.

Roughly 3 million hectares of crop land were impacted. Loss and Damage estimates for agriculture included 3.1M bales of cotton, 1.8Mt of rice and 10.5Mt of sugar cane. Not only were these crops lost leaving farmers with no revenue and increased food insecurity, but the damaged crops most likely led to significant GHGs as they rotted in wet fields.

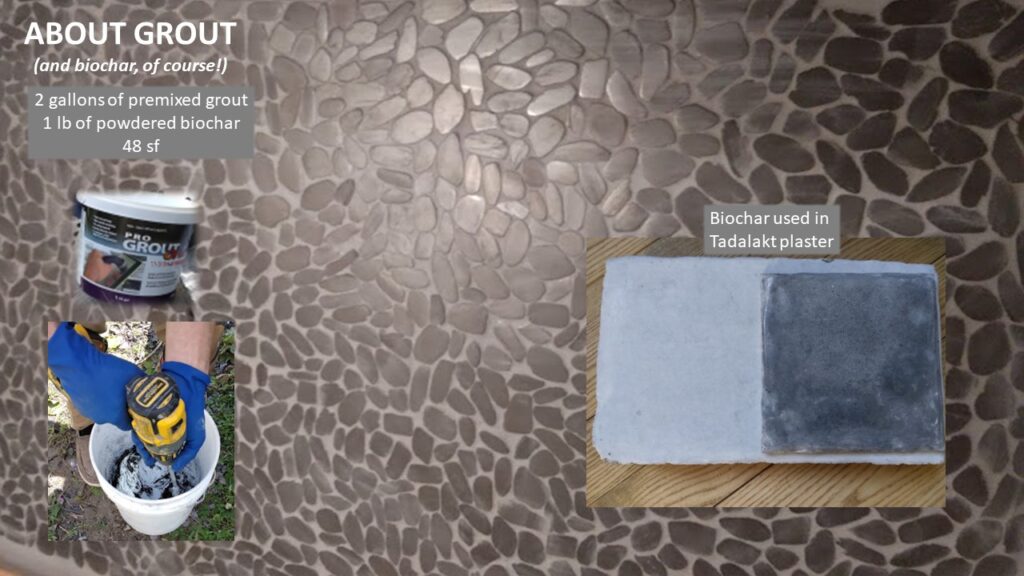

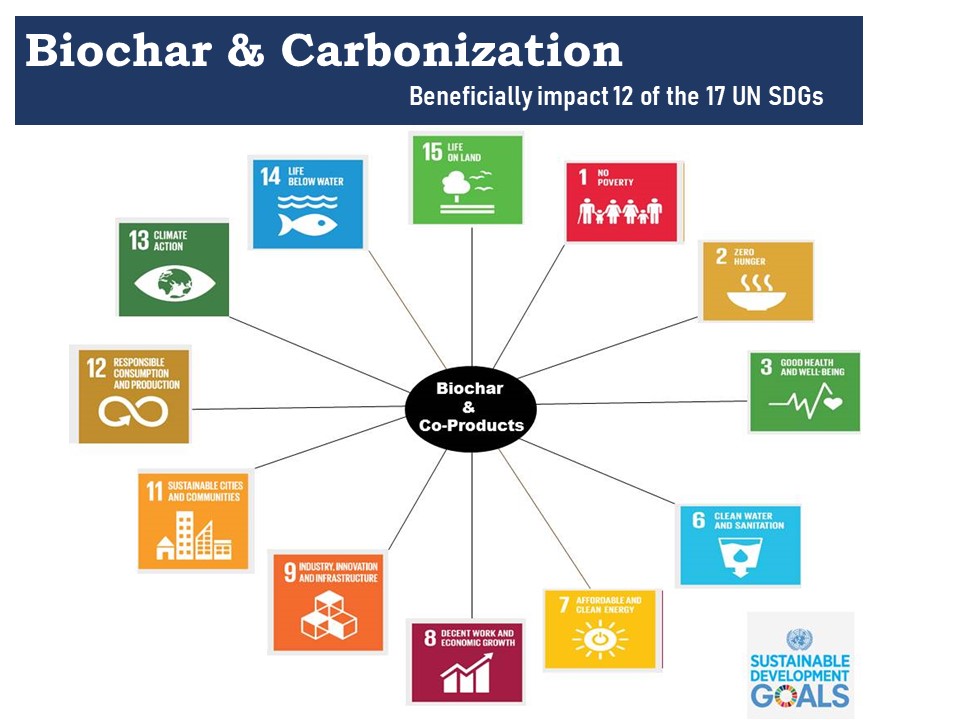

Now imagine if there was a way to finance the collection and carbonization of rotting residues (I acknowledge that drying during wet seasons is a significant challenge). Given the growing number of biochar-based carbon removal methodologies and growing demand for removal credits, it may now be possible to fund some sort of biochar focused disaster recovery effort using portable carbonization equipment, some of which may be able to provide needed electricity and/or heat. This could provide numerous jobs for displaced people and the biochar could be used to replenish lost soil carbon or filter water or remediate toxins or any number of other uses depending on what the most pressing needs are post-disaster.

Large multi-national corporations that are dependent on the crops could purchase these credits which will help farmers to recover faster and hopefully incentivize them to stay in farming. Or countries could purchase removal credits from the impacted countries as a mechanism of meeting their NDC targets.

Perhaps an organization such as the UN Central Emergency Response Fund could act as a facilitator, broker or verification agency when it comes to understanding the potential biomass impacted and available for carbonization. And perhaps organizations such as Rotary or Samaritan’s Purse could train locals on how to make and use biochar in the most pragmatic way based on the specific impacts from the disaster.

Biochar production from disaster debris is already happening but at very small scale in Puerto Rico and the Philippines and likely elsewhere as well. Given the increasing number and scale of climate disasters, I’d say there is no better time than now to develop this idea and test the waters for funding!