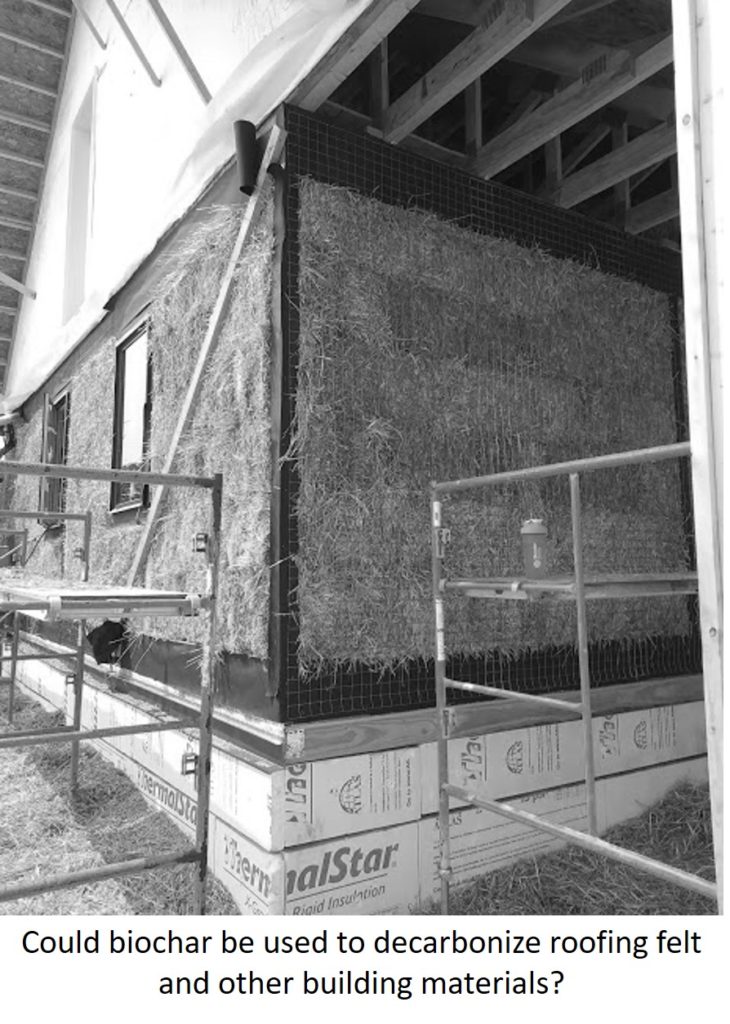

Last week marked my first big step in my latest project (and perhaps next book) which I’ve dubbed “dwelling on drawdown”. It involves researching, designing and building my forever home with an eye towards maximizing carbon sequestration and minimizing the use of fossil fuels in my c-sink sanctuary and surrounding yard. The scope will incorporate embodied carbon (for materials used during the build phase) and operating carbon (carbon used once the home is operating). My first big step consisted of attending an incredibly well-run week-long workshop where 43 folks from around the globe gathered to learn and help build a strawbale house. It was interesting, illuminating and a bit itchy!

Although my main focus for years has been on biochar, there are other materials that can also serve as C-sinks. Straw is one example, hemp another. According to one study, the ratio of carbon sequestration to weight of straw (at 10% moisture) is ~1.35:1.00. Using an average weight of 45 lbs/bale (60.76 lbs CO2), the house we built last week stored nearly 10t of Co2 (320 bales of straw were used). Factoring the embodied carbon (a life cycle assessment perspective) would require a lot more info on how the straw was harvested, transported, etc. Although the sequestration impact of wood is higher on a per pound basis (1.83:1.00 according to this study), the time value of carbon absorption ought to be factored in. Crop residues such as straw and hemp are especially appealing as they are annually renewable. The use of such residues also supports local farming communities.

Could biochar provide a larger carbon sink option per square foot for building walls? In all likelihood it could, but the current early stage of biochar building materials (e.g. bricks, mortar) makes building a predominantly biochar-based house a bit premature at this stage. I also appreciate that the full amount of carbon pulled from the atmosphere from wheat (or rice, barley, etc.) and hemp can be stored for long periods. When carbonized, you lose up to half of that carbon so these materials offer great carbon rebalancing opportunities when stored in buildings.

While the straw bale building process is generally quite sustainable, there are potential opportunities for biochar-based building materials to decarbonize some of the ancillary materials and processes used. Here are just a few ideas:

Roofing felt: we used a fair amount of roofing felt on both the interior and exterior walls, predominantly to cover wood and provide a more textured surface for applying plaster. Normally this material, also referred to as underlayment, tar paper (similar though not exactly the same) or membrane roofing, is used underneath asphalt shingles. The market is not trivial, supposedly $11B in 2016, no doubt this is due to its use in both reroofing and new construction. Roofing felt is a petroleum product; the cellulose felt is drenched in bitumen/asphalt to render it waterproof. It is on my hit list for elimination if at all possible as it comes with not only CO2 emissions during production, but VOC emissions after application.

Could we perhaps develop ‘char paper’ using bio-oil to facilitate water repelling properties? (To be honest, I have no idea if bio-oil can produce that type of result, but am happy to throw out the idea for chemists to ponder more profoundly.) Thicker carbon felt is already used for various things including fire resistant welding blankets, thermal insulators and more. Substituting lower cost biochar made from unloved organic material would provide a great opportunity for decarbonizing roofing materials.

Weed whip string – another aspect of straw bale building which could use a decarb make-over is the use of weed whip string which is used to smooth out the exterior of the bales before plaster is applied. With half a dozen string trimmers buzzing at the same time, a heck of a lot of micro-plastic flakes were being flung far and wide, polluting air, water and soil. Biochar is already being tested in 3D printing filament which looks very similar to trimmer string. No doubt there are different performance requirements, but surely binders exist that could produce strings with the relevant characteristics. Flinging out bits of biochar would undoubtably be better for flora and fauna.

New York has recently risen to the challenge of climate change legislation and is striving towards a zero carbon economy by 2050. The focus seems to be on eliminating operational carbon (i.e. fossil fuel used for energy production). However, we cannot ignore the carbon needed for creating buildings, infrastructure and transportation. Turning these into sinks instead of sources of high embodied carbon products is a challenge which brings with it enormous opportunity for creativity and job creation.