One of the biggest fears that one hears about biochar is related to the food versus fuel debate. The thinking goes that in order for biochar to make a significant contribution to reducing atmospheric carbon levels, huge swaths of land would need to be planted with fast growing, high lignin biomass such as bamboo. On the flip side of the debate is that with an ever increasing number of humans, more and more land will likely be needed for growing food. (Somehow all the acreage dedicated to cotton – more than 11 million acres in the US alone – never seems to come up and I’m just not convinced we need more cotton t-shirts when so many fabrics made from recycled materials are available. But I digress…)

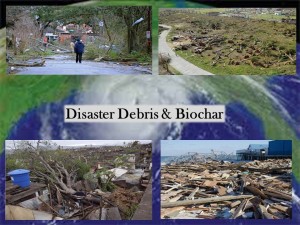

Considering the increasing number of devastating climate events that are felling forests (and buildings) faster and faster, it seems to me that Mother Nature, in her moments of ire, is providing plenty of carbon fodder which could be used for sequestration. Debris from these ‘natural’ disasters often gets shipped off to landfills. Some, including the Rocky Mountain Institute, are advocating for this kind of debris to be shipped off to biomass generators to offset fossil fuel energy generation. A better if not best option IMHO.

Hurricanes Katrina & Rita alone were responsible for killing 320 MILLION trees. I have absolutely no idea how much carbon each tree might have had on its dying day, but I do know that all of that will go back into the atmosphere if it is chipped & burned.

Let’s ponder the possibilities of pyrolyzing these piles for a moment. I posed the question to a forestry friend of mine last night and just for giggles, we assumed the average tree weight was 1,600 lbs and 25% was carbon or 400 lbs per tree. Converting this biomass to biochar could sequester up to half of that carbon which would be something like 64,000,000,000 lbs of Carbon. Then do the math on the CO2 equivalent for that carbon and we arrived at the exact figure of ‘nothing to sneeze at’ especially when you consider the alternatives!

At the same time the biochar produced can be used to rebuild the soils that have been damaged by sewage or other bio-hazards. As an example Tropical Storm Irene damaged more than 20,000 acres of farm land in Vermont alone and washed away countless tons of topsoil. Biochar could have helped to restore much of that damage and prevent plants from taking up some of the toxins.

One of my latest projects includes working with an incredibly knowledgeable retired FEMA manager on the design of a scalable template for debris management which includes biochar. The model is looking at how communities could/should include biochar in not only disaster or emergency management of debris, but on-going management of yard debris. Next up we are planning to design a prioritized list of end-uses for the biochar based on the needs of the community. The ways that biochar can be used are not limited to remediating or rebuilding eroded soils, but can include use as a building material to rebuild homes, retaining walls and several other long-lasting products.

With the increasing number of affordable and portable technologies available which can convert wood chips into heat, electricity and biochar, I can see the day when many disaster-prone communities have a pyrolysis unit at the ready to handle ice storm debris, tornado detritus, or the wreckage which follows hurricanes. Turning the downed biomass into biochar could go a long way towards helping both communities and the planet to recover.